These Reviews appeared first in The Journal of Architectural Education

Index

Review: Bad Bunny

At the End of the Tunnel:Bad Bunny’s Vid(e)ocumentary Sheds Light (and Music) into Boricuas’ Struggle against Dispossession

Juan Carlos Quiñones

Review:

“El Apagón - Aquí Vive Gente”

Bad Bunny

Juan Carlos Quiñones

Review:

“El Apagón - Aquí Vive Gente”

Bad Bunny

Soundscape: la clave. A beat of bomba rhythm. Bomba is the first autochthonous music of Puerto Rico, created by enslaved Black people, forcibly and violently brought from different parts of Africa to be exploited for labor in the sugar plantations more than 400 years ago. It is a quintessential expression of Puerto Rican cultural identity, and it has survived every attempt at eradication by the powers that be.

Seascape/landscape: An aerial drone view hovers over a shoreline. To the left, the Atlantic Ocean, waves crashing on the shore of a rocky beach. To the extreme right, Calle Norzagaray, the frontier-street that separates El Viejo San Juan from La Perla. El Viejo San Juan, Old San Juan, is the colonial city, a world-renowned tourist destination. Some of the buildings shown here are probably properties currently owned by foreign investors benefiting from Act 60 (previously known as “Act 20-2022”), the Individual Investors Act, designed to attract wealthy investors from other countries. Surely, most of these properties have by now been repurposed to be rented to tourists—especially as Airbnbs, which have taken hold of the once primarily local-owned properties. Dead Center: La Perla, The Pearl. This slum or shantytown community was established during the eighteenth century by slaves, proletarians, and people of the lower classes on the margins of the main colonial city. Historically, it has been a locus of class struggle, social and economic inequality resulting in conflict and sometimes violence, as the small but lively population has been neglected and systematically discriminated against. Recently, the exponential increase in properties bought by foreign investors has brought a wave of sometimes unfriendly and undesired tourism to the El Hoyo neighborhood, and has attracted the interest of further foreign investment and capital in the area. Tourist-oriented bars, discos, and restaurants have proliferated. Originally the product of gentrification, the community sees itself a victim of gentrification once again. This aerial view visually synthesizes the dynamics of race, colonialism, capitalism, exploitation, gentrification, displacement, inequality, and oppression that are taking place on our island.

As is the rest of the island, La Perla is a battleground.

Testimony/Impression/Subjective

The first time I watched Bad Bunny’s video “El apagón/Aquí vive gente”(“The Blackout/People Live Here” in that other language) I was in transit. I was riding the AMA bus (AMA stands for Autoridad Metropolitana de Autobuses, the dramatically unreliable public transportation system) from my apartment in el caserío Residencial Luis Llorens Torres (a sprawling public housing project) to El Viejo San Juan, where I sometimes stay with my partner. It was early afternoon, and I noticed that other people in the bus were watching the video simultaneously. The news of the video’s release went viral almost instantaneously, and the collective feeling was one of pompeaera (a heightened sense of excitement), an all-too-fleeting sense of communal belonging, and a deep feeling of pride. The atmosphere (both in the physical and the social media realms) was familiar. It felt just the way we boricuas feel when the island’s contestant for the Miss Universe pageant wins the crown (it happens often), when we kick everybody’s ass in sports (it happens often), or when, well, one of our supernaturally talented artists makes it big on the world stage. Like Bad Bunny, for example. We feel proud. As the introduction of the video establishes unequivocally: “A nosotros nos sale natural ser leyenda. Porque al final, no hay orgullo más grande que decir, después de cada logro ‘yo soy de P fuckin’ R’.” (“Being legendary comes to us naturally. Because in the end, there’s no greater pride than to say, after each achievement ‘I’m from P fuckin’ R’.”)

As soon as I got home, I summoned the tribe (my partner, her brother, and her nieces), and we all gathered to watch the video on a big screen. I think we watched it at least three consecutive times. We sang. We laughed. We danced. We made jokes, poked fun at the neocolonizers and politicians portrayed in the documentary. We discussed different aspects of the piece. And we embraced. It felt like hope. Don’t expect total objectivity from this reviewer.

Because less than an hour after the viewing (and as it happens all too often nowadays in Puerto Rico), the lights went out. Another apagón leaves us all again in total darkness.

Puerto Rico está bien cabrón (Puerto Rico is fucking great)

After an introduction in which we see footage of sold-out concerts establishing the enormous fandom of the singer, interspersed with quick images of Bad Bunny’s participation in the massive protests during what has become known as el verano del ‘19 (“The Summer of ‘19”), the first section of the music video shows Bad Bunny singing along with individual people of all ages, genders, and identities mouthing the lyrics of the song. The song and the video both make references to distinguished superstar figures of our sports and music pantheons such as Puerto Rican musician Tego Calderón and J. J. Barea, an NBA basketball player.

And then, boom!!

Boom

With the fiery explosion of a power plant, the video becomes a documentary-exposé called “Aquí vive gente,” featuring the reporting of local investigative journalist Bianca Graulau, a Puerto Rican independent journalist. The power plant in question is a main supplier of energy to the island. Immediately, Graulau describes how—with a criminal, cynical negligence and a lack of honesty—the government privatized the electrical grid by selling it to a foreign private company, promising that service would improve. LUMA, the North American company that bought the Autoridad de Energía Eléctrica (AEE), didn’t deliver as promised; even worse, it increased the cost of electricity for all. Not only did service not improve, it got abysmally worse. This part of the documentary ends with the journalist reporting on the dissatisfaction and anger that Puerto Ricans feel over the sellout. Simultaneously, there is footage of several marches and protests, some of them massive. People took to the streets, denouncing privatization, LUMA’s role in the people’s suffering, and the uncertainty of the power service.

Graulau’s presence is significant because as an independent journalist she works outside the world of local news outlets, and doesn’t respond to the agendas of mainstream media, which is known to be unreliable and biased. The importance of this “sucker punch” political strategy cannot be overstated. This insertion is totally unexpected and very effective, as it allows for the documentary (and its public denunciation of government policy) to reach a maximum audience.

Maldita sea, otro apagón (Goddammit, Another Blackout)

After this interlude, Bad Bunny comes back with a literal vengeance, viscerally expressing Puerto Ricans’ anger and frustration with the constant blackouts that torment the population and announcing his desire to slap the current governor of the island, Pedro Pierluisi. “Vamo’ pa’ lo’ bleacher a prender un blunt / antes que a Pipo le dé un bofetón,” warns the singer (“Let’s go to the bleachers to light up a blunt / before Pipo gets a slap in the face.”. “Pipo” is the generalized derogatory nickname that Puerto Ricans have given the governor by consensus.

While the lyrics of the song work as free-floating signifiers, clichés of pop music, the regaettón genre and the celebration of the island’s encantos (wonders) that can be taken as banal and frivolous in themselves, the images of the video anchor three words, charging them with a powerful political message. By itself, the line “El sol es Taíno” (“The sun is Taíno”) can be taken as just a glorified reference to the Caribbean Paradise that Puerto Rico signifies in a specific touristic imaginary. But when Bad Bunny is singing those words, we fleetingly see an iconic image: an artistic depiction of the drowning of Salcedo. This is a folkloric Puerto Rican story based on the idea that the Taínos (the Indigenous inhabitants of the island) thought that the Spanish colonizers were white gods. Wanting to prove or disprove this theory, a group of Taínos approach a Spanish soldier and offer to help him cross a river. While in the middle of the stream, the men push the Spaniard underwater until (of course) he drowns, showing that these people were just men and not gods, dissipating the fear that prevented the Taínos from fighting back against the genocidal European invaders. The seemingly innocuous phrase takes a more ominous meaning accompanied by this image.

Somos más y no tenemos miedo (We Are More, and We Ain’t Afraid): The Summer of ‘19

“El apagón” came out as part of the record called Un verano sin ti (A Summer Without You), released on May 6, 2022. (A corny expression of spite and of longing for a lost lover, it is an allusive reference to the unprecedented series of revolutionary protests in Summer 2019 that forced the then-governor of Puerto Rico, Ricardo Roselló, to resign. Bad Bunny played a significant role in solidarity with the people’s plight).[i] With this allusion, the album title becomes a warning to the current governor, Pierluisi, implying that he must change his oppressive political ways. It works as the expression of longing for a time when he is no longer the governor of the island. The reference to the current governor’s role and liability in the mess of criminal negligence in the issue of privatization will be made explicit in the second part of the music video. BOOM!!, with a literal bang, comes the first part of the documentary summarized above. “Somos más y no tenemos miedo” (“we are more, and we ain’t afraid”) was the slogan that expressed the anger and defiance of the Puerto Rican people during the protests.

Me gusta la chocha de Puerto Rico (I Like the Pussy of Puerto Rico): The Revolution Will be a Hip-Hop Party

The next part of the video starts with footage of people on motorcycles and ATVs heading to a party. Again, a commonplace and stock trope of regaettón videos gets resignified in the context of the el verano del ‘19, when hundreds of motorists from all around the islands participated in the protests en masse organized by a man nicknamed “Rey Charlie.”

They get to an underground tunnel where a rave party is taking place, with Bad Bunny as the singer, singing “Puerto Rico está bien cabrón” once again. Some partygoers are brandishing flashlights in obvious reference to the constant blackouts endured by the population. Again, there are young people of all races, genders, and identities, with strong representation of queer and Black people dancing. The Black Puerto Rican flag, a symbol of resistance during el verano del ’19 and ever since, and the rainbow LGBTQ pride flag are being waved by people in the crowd. This is a party, though. The people are dancing, frenetically in some instances, with a lot of pleasurable and sexual overtones. Like the perreo combativo, I read this party as a political action, as a joyful form of rebellion against the oppressive and criminal status quo that leaves us literally in the dark. This form of “joyful protest” is transgressive not only to the powers that be (the purpose of the gathering is to protest, to express anger and frustration and to demand change) and the capitalist logic of the opposition between “work and play,” but also to the orthodoxy of the most rigid and rancid sectors of the political left that frown upon such joyful expressions of dissent. This type of action is radical even to them.

Yo creo que el público sabe que esto es una cosa má’ o meno’ informal (I Think the Public Knows This Is a Sort of Informal Thing): There’s Light at the End of the Tunnel

In the last part of the music video, the rave party is winding down and we hear an MC’s voice saying matter-of-factly: “Yo creo que el público sabe que esto es una cosa má’ o meno’ informal” Then we see a young woman swaying to the suddenly mellow music and singing the following lyrics:

Yo no me quiero ir de aquí

que se vayan ellos

lo que me pertenece a mi

se lo quedan ellos

que se vayan ellos

(I don’t want to leave this place

let THEM go

what belongs to me

they keep for themselves

let THEM go).

The words speak for themselves.

The rave party is over. It is dawn, and people are coming out of the tunnel to a beautiful beach with palm trees and sand. The people seem exhausted and contented, and we see same-sex and opposite-sex couples strolling through the beach. The atmosphere is relaxed, contented, blissful. Establishing the parallelism between joy and political action, we get glimpses of the protests of el verano del ’19 (we also get the contrast of the potential for violence between the police forces of repression and the protesters) and finally, brief footage of Bad Bunny’s participation during the protests, standing on top of a van and waving a large Puerto Rican flag. Between snippets of drone footage depicting the shore, again we see glimpses of diverse people smiling. We hear a sweet and melodic female voice singing:

Esta es mi playa

este es mi sol

esta es mi tierra

esta soy yo

(This is my beach

this is my sun

this is my land

this is me)

I think that it is in that last line (“this is me”) where the strongest political argument takes place. By identifying the “body of the island” and “my body,” some of the lyrics that come before acquire political meaning. The “Puerto Rico está bien cabrón” line gives a voice of pride to the body of the island. It is the island speaking. “Me gusta la chocha de Puerto Rico,” far from being a disrespectful vulgarity, becomes a declaration of lustful, joyful, erotic love and desire for the island. With the phrase “Yo creo que el público sabe que esto es una cosa má’ o meno’ informal,” all this wording deploys what I call a pragmatic of politics, body politics, and post-ideological politics of common sense. Like the “normal” that Bad Bunny repeats in his lyrics from time to time, this language points toward a radical political positioning beyond traditional politics, extremely critical of the agendas of the traditional political parties and a politics of direct action, movement, and activism.

Que se vayan ellos/Aquí vive gente

Journalist Bianca Graulau returns with an exploration of the damning effects of gentrification upon the communities of Puerta de Tierra and Dorado, respectively, due in part to Act 60 and an influx of private foreign developers. She interviews people from the communities, community leaders, workers, politicians, and activists who give their take on the issues. In a very clear and educational way and by using simple visual resources, she explains how American foreign investors have bought a lot of properties in the barrio of Puerta de Tierra, displacing dozens of longtime residents and skyrocketing rental and sale prices of housing. These neocolonizers are taking advantage of Act 60, a law that unfairly benefits foreigners by exempting them from paying capital gain taxes, making Puerto Rico a haven of cryptocurrency millionaires and investors. In Dorado, she reports on how private touristic developers have appropriated public beaches, making it impossible for locals to enjoy the beaches and turning them into de facto private properties. She also reports on the actions of community groups and activists who resist these oppressive forces.

Illuminating (Other) Geographies: Impact on Latin America and the Rest of the World

It is fair to ask how effective “El apagón” is as a political tool, and how impactful its strategies are in terms of conveying its political message. Some statistics would be helpful. Un verano sin ti, the album in which the song appears, was streamed a record-breaking two billion times in the first month of its release. The vid(e)ocumentary itself has been viewed eight million times—701,368 times to the date of this review (full disclosure: a couple of hundred of those viewings may have been by this reviewer). The public reception of “El apagón” has been overwhelmingly positive. The video has more than 26,000 comments on YouTube. I decided to browse through them. What I discovered was astonishing.

In general, viewers’ reactions to the video can be divided into three groups: solidarity with the Puerto Rican plight and struggle against capitalism and the United States’ colonial regime, comparisons between Puerto Rico’s struggle and the situation of privatization in the commentators’ own countries, and expressions of how the documentary has ‘opened their eyes’ to new political realities. In different countries, people are taking the vid(e)ocumentary message and are applying it to their own personal and collective experiences in their places of origin. This outpouring of solidarity and awareness is not limited to Latin America: I found comments from different countries in Africa, Europe, and Asia as well. If this becomes a trend (I hope it does), this kind of pop-political artifact could be added to the arsenal of political activism, with global reach and tangible potential for change.

Note

[1]. For an analysis of these protests see Luis Othoniel Rosa, “Pensar en panal: Apuntes sobre las protestas masivas en Puerto Rico, Julio 2019,” first published in Puerto Rico Review (http://www.thepuertoricoreview.com/rickyrenuncia) and later in Ediciones Mimesis, August 7, 2019.

Author Bio:

Juan Carlos Quiñones (Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, 1972) is a novelist, essayist, translator, and editor. He studied literature and philosophy at the University of Puerto Rico. His texts have been published in Puerto Rican, Latin American, Spanish, and North American magazines and anthologies, both in print and electronically. He is a regular contributor to the magazine 80 Grados+, Revista Plenamar (Dominican Republic), and was a co-editor of the Latin American electronic literary magazine Letralia. In addition to the novel Adelaida recupera su peluche (How Adelaida Got Her Stuffed Toy Back) he has published the prose books Breviario and Todos los nombres el nombre (All The Names in a Name), the novel Bar Schopenhauer, and the children’s novel El libro del tapiz iluminado (The Book of Illuminated Tapestry). His books have been recognized in the competitions of the Pen Club of Puerto Rico, El barco de vapor, and the Institute of Puerto Rican Literature.

How to Cite This: Quiñones, Juan Carlos. Review of “El apagón/Aquí Vive Gente,” by Bad Bunny, JAE Online. This music video was released on September 16, 2022. It is an audiovisual project and documentary directed by Kacho Lopez Marii and incorporating reporting by journalist Bianca Graulau.

Seascape/landscape: An aerial drone view hovers over a shoreline. To the left, the Atlantic Ocean, waves crashing on the shore of a rocky beach. To the extreme right, Calle Norzagaray, the frontier-street that separates El Viejo San Juan from La Perla. El Viejo San Juan, Old San Juan, is the colonial city, a world-renowned tourist destination. Some of the buildings shown here are probably properties currently owned by foreign investors benefiting from Act 60 (previously known as “Act 20-2022”), the Individual Investors Act, designed to attract wealthy investors from other countries. Surely, most of these properties have by now been repurposed to be rented to tourists—especially as Airbnbs, which have taken hold of the once primarily local-owned properties. Dead Center: La Perla, The Pearl. This slum or shantytown community was established during the eighteenth century by slaves, proletarians, and people of the lower classes on the margins of the main colonial city. Historically, it has been a locus of class struggle, social and economic inequality resulting in conflict and sometimes violence, as the small but lively population has been neglected and systematically discriminated against. Recently, the exponential increase in properties bought by foreign investors has brought a wave of sometimes unfriendly and undesired tourism to the El Hoyo neighborhood, and has attracted the interest of further foreign investment and capital in the area. Tourist-oriented bars, discos, and restaurants have proliferated. Originally the product of gentrification, the community sees itself a victim of gentrification once again. This aerial view visually synthesizes the dynamics of race, colonialism, capitalism, exploitation, gentrification, displacement, inequality, and oppression that are taking place on our island.

As is the rest of the island, La Perla is a battleground.

Testimony/Impression/Subjective

The first time I watched Bad Bunny’s video “El apagón/Aquí vive gente”(“The Blackout/People Live Here” in that other language) I was in transit. I was riding the AMA bus (AMA stands for Autoridad Metropolitana de Autobuses, the dramatically unreliable public transportation system) from my apartment in el caserío Residencial Luis Llorens Torres (a sprawling public housing project) to El Viejo San Juan, where I sometimes stay with my partner. It was early afternoon, and I noticed that other people in the bus were watching the video simultaneously. The news of the video’s release went viral almost instantaneously, and the collective feeling was one of pompeaera (a heightened sense of excitement), an all-too-fleeting sense of communal belonging, and a deep feeling of pride. The atmosphere (both in the physical and the social media realms) was familiar. It felt just the way we boricuas feel when the island’s contestant for the Miss Universe pageant wins the crown (it happens often), when we kick everybody’s ass in sports (it happens often), or when, well, one of our supernaturally talented artists makes it big on the world stage. Like Bad Bunny, for example. We feel proud. As the introduction of the video establishes unequivocally: “A nosotros nos sale natural ser leyenda. Porque al final, no hay orgullo más grande que decir, después de cada logro ‘yo soy de P fuckin’ R’.” (“Being legendary comes to us naturally. Because in the end, there’s no greater pride than to say, after each achievement ‘I’m from P fuckin’ R’.”)

As soon as I got home, I summoned the tribe (my partner, her brother, and her nieces), and we all gathered to watch the video on a big screen. I think we watched it at least three consecutive times. We sang. We laughed. We danced. We made jokes, poked fun at the neocolonizers and politicians portrayed in the documentary. We discussed different aspects of the piece. And we embraced. It felt like hope. Don’t expect total objectivity from this reviewer.

Because less than an hour after the viewing (and as it happens all too often nowadays in Puerto Rico), the lights went out. Another apagón leaves us all again in total darkness.

Puerto Rico está bien cabrón (Puerto Rico is fucking great)

After an introduction in which we see footage of sold-out concerts establishing the enormous fandom of the singer, interspersed with quick images of Bad Bunny’s participation in the massive protests during what has become known as el verano del ‘19 (“The Summer of ‘19”), the first section of the music video shows Bad Bunny singing along with individual people of all ages, genders, and identities mouthing the lyrics of the song. The song and the video both make references to distinguished superstar figures of our sports and music pantheons such as Puerto Rican musician Tego Calderón and J. J. Barea, an NBA basketball player.

And then, boom!!

Boom

With the fiery explosion of a power plant, the video becomes a documentary-exposé called “Aquí vive gente,” featuring the reporting of local investigative journalist Bianca Graulau, a Puerto Rican independent journalist. The power plant in question is a main supplier of energy to the island. Immediately, Graulau describes how—with a criminal, cynical negligence and a lack of honesty—the government privatized the electrical grid by selling it to a foreign private company, promising that service would improve. LUMA, the North American company that bought the Autoridad de Energía Eléctrica (AEE), didn’t deliver as promised; even worse, it increased the cost of electricity for all. Not only did service not improve, it got abysmally worse. This part of the documentary ends with the journalist reporting on the dissatisfaction and anger that Puerto Ricans feel over the sellout. Simultaneously, there is footage of several marches and protests, some of them massive. People took to the streets, denouncing privatization, LUMA’s role in the people’s suffering, and the uncertainty of the power service.

Graulau’s presence is significant because as an independent journalist she works outside the world of local news outlets, and doesn’t respond to the agendas of mainstream media, which is known to be unreliable and biased. The importance of this “sucker punch” political strategy cannot be overstated. This insertion is totally unexpected and very effective, as it allows for the documentary (and its public denunciation of government policy) to reach a maximum audience.

Maldita sea, otro apagón (Goddammit, Another Blackout)

After this interlude, Bad Bunny comes back with a literal vengeance, viscerally expressing Puerto Ricans’ anger and frustration with the constant blackouts that torment the population and announcing his desire to slap the current governor of the island, Pedro Pierluisi. “Vamo’ pa’ lo’ bleacher a prender un blunt / antes que a Pipo le dé un bofetón,” warns the singer (“Let’s go to the bleachers to light up a blunt / before Pipo gets a slap in the face.”. “Pipo” is the generalized derogatory nickname that Puerto Ricans have given the governor by consensus.

While the lyrics of the song work as free-floating signifiers, clichés of pop music, the regaettón genre and the celebration of the island’s encantos (wonders) that can be taken as banal and frivolous in themselves, the images of the video anchor three words, charging them with a powerful political message. By itself, the line “El sol es Taíno” (“The sun is Taíno”) can be taken as just a glorified reference to the Caribbean Paradise that Puerto Rico signifies in a specific touristic imaginary. But when Bad Bunny is singing those words, we fleetingly see an iconic image: an artistic depiction of the drowning of Salcedo. This is a folkloric Puerto Rican story based on the idea that the Taínos (the Indigenous inhabitants of the island) thought that the Spanish colonizers were white gods. Wanting to prove or disprove this theory, a group of Taínos approach a Spanish soldier and offer to help him cross a river. While in the middle of the stream, the men push the Spaniard underwater until (of course) he drowns, showing that these people were just men and not gods, dissipating the fear that prevented the Taínos from fighting back against the genocidal European invaders. The seemingly innocuous phrase takes a more ominous meaning accompanied by this image.

Somos más y no tenemos miedo (We Are More, and We Ain’t Afraid): The Summer of ‘19

“El apagón” came out as part of the record called Un verano sin ti (A Summer Without You), released on May 6, 2022. (A corny expression of spite and of longing for a lost lover, it is an allusive reference to the unprecedented series of revolutionary protests in Summer 2019 that forced the then-governor of Puerto Rico, Ricardo Roselló, to resign. Bad Bunny played a significant role in solidarity with the people’s plight).[i] With this allusion, the album title becomes a warning to the current governor, Pierluisi, implying that he must change his oppressive political ways. It works as the expression of longing for a time when he is no longer the governor of the island. The reference to the current governor’s role and liability in the mess of criminal negligence in the issue of privatization will be made explicit in the second part of the music video. BOOM!!, with a literal bang, comes the first part of the documentary summarized above. “Somos más y no tenemos miedo” (“we are more, and we ain’t afraid”) was the slogan that expressed the anger and defiance of the Puerto Rican people during the protests.

Me gusta la chocha de Puerto Rico (I Like the Pussy of Puerto Rico): The Revolution Will be a Hip-Hop Party

The next part of the video starts with footage of people on motorcycles and ATVs heading to a party. Again, a commonplace and stock trope of regaettón videos gets resignified in the context of the el verano del ‘19, when hundreds of motorists from all around the islands participated in the protests en masse organized by a man nicknamed “Rey Charlie.”

They get to an underground tunnel where a rave party is taking place, with Bad Bunny as the singer, singing “Puerto Rico está bien cabrón” once again. Some partygoers are brandishing flashlights in obvious reference to the constant blackouts endured by the population. Again, there are young people of all races, genders, and identities, with strong representation of queer and Black people dancing. The Black Puerto Rican flag, a symbol of resistance during el verano del ’19 and ever since, and the rainbow LGBTQ pride flag are being waved by people in the crowd. This is a party, though. The people are dancing, frenetically in some instances, with a lot of pleasurable and sexual overtones. Like the perreo combativo, I read this party as a political action, as a joyful form of rebellion against the oppressive and criminal status quo that leaves us literally in the dark. This form of “joyful protest” is transgressive not only to the powers that be (the purpose of the gathering is to protest, to express anger and frustration and to demand change) and the capitalist logic of the opposition between “work and play,” but also to the orthodoxy of the most rigid and rancid sectors of the political left that frown upon such joyful expressions of dissent. This type of action is radical even to them.

Yo creo que el público sabe que esto es una cosa má’ o meno’ informal (I Think the Public Knows This Is a Sort of Informal Thing): There’s Light at the End of the Tunnel

In the last part of the music video, the rave party is winding down and we hear an MC’s voice saying matter-of-factly: “Yo creo que el público sabe que esto es una cosa má’ o meno’ informal” Then we see a young woman swaying to the suddenly mellow music and singing the following lyrics:

Yo no me quiero ir de aquí

que se vayan ellos

lo que me pertenece a mi

se lo quedan ellos

que se vayan ellos

(I don’t want to leave this place

let THEM go

what belongs to me

they keep for themselves

let THEM go).

The words speak for themselves.

The rave party is over. It is dawn, and people are coming out of the tunnel to a beautiful beach with palm trees and sand. The people seem exhausted and contented, and we see same-sex and opposite-sex couples strolling through the beach. The atmosphere is relaxed, contented, blissful. Establishing the parallelism between joy and political action, we get glimpses of the protests of el verano del ’19 (we also get the contrast of the potential for violence between the police forces of repression and the protesters) and finally, brief footage of Bad Bunny’s participation during the protests, standing on top of a van and waving a large Puerto Rican flag. Between snippets of drone footage depicting the shore, again we see glimpses of diverse people smiling. We hear a sweet and melodic female voice singing:

Esta es mi playa

este es mi sol

esta es mi tierra

esta soy yo

(This is my beach

this is my sun

this is my land

this is me)

I think that it is in that last line (“this is me”) where the strongest political argument takes place. By identifying the “body of the island” and “my body,” some of the lyrics that come before acquire political meaning. The “Puerto Rico está bien cabrón” line gives a voice of pride to the body of the island. It is the island speaking. “Me gusta la chocha de Puerto Rico,” far from being a disrespectful vulgarity, becomes a declaration of lustful, joyful, erotic love and desire for the island. With the phrase “Yo creo que el público sabe que esto es una cosa má’ o meno’ informal,” all this wording deploys what I call a pragmatic of politics, body politics, and post-ideological politics of common sense. Like the “normal” that Bad Bunny repeats in his lyrics from time to time, this language points toward a radical political positioning beyond traditional politics, extremely critical of the agendas of the traditional political parties and a politics of direct action, movement, and activism.

Que se vayan ellos/Aquí vive gente

Journalist Bianca Graulau returns with an exploration of the damning effects of gentrification upon the communities of Puerta de Tierra and Dorado, respectively, due in part to Act 60 and an influx of private foreign developers. She interviews people from the communities, community leaders, workers, politicians, and activists who give their take on the issues. In a very clear and educational way and by using simple visual resources, she explains how American foreign investors have bought a lot of properties in the barrio of Puerta de Tierra, displacing dozens of longtime residents and skyrocketing rental and sale prices of housing. These neocolonizers are taking advantage of Act 60, a law that unfairly benefits foreigners by exempting them from paying capital gain taxes, making Puerto Rico a haven of cryptocurrency millionaires and investors. In Dorado, she reports on how private touristic developers have appropriated public beaches, making it impossible for locals to enjoy the beaches and turning them into de facto private properties. She also reports on the actions of community groups and activists who resist these oppressive forces.

Illuminating (Other) Geographies: Impact on Latin America and the Rest of the World

It is fair to ask how effective “El apagón” is as a political tool, and how impactful its strategies are in terms of conveying its political message. Some statistics would be helpful. Un verano sin ti, the album in which the song appears, was streamed a record-breaking two billion times in the first month of its release. The vid(e)ocumentary itself has been viewed eight million times—701,368 times to the date of this review (full disclosure: a couple of hundred of those viewings may have been by this reviewer). The public reception of “El apagón” has been overwhelmingly positive. The video has more than 26,000 comments on YouTube. I decided to browse through them. What I discovered was astonishing.

In general, viewers’ reactions to the video can be divided into three groups: solidarity with the Puerto Rican plight and struggle against capitalism and the United States’ colonial regime, comparisons between Puerto Rico’s struggle and the situation of privatization in the commentators’ own countries, and expressions of how the documentary has ‘opened their eyes’ to new political realities. In different countries, people are taking the vid(e)ocumentary message and are applying it to their own personal and collective experiences in their places of origin. This outpouring of solidarity and awareness is not limited to Latin America: I found comments from different countries in Africa, Europe, and Asia as well. If this becomes a trend (I hope it does), this kind of pop-political artifact could be added to the arsenal of political activism, with global reach and tangible potential for change.

Note

[1]. For an analysis of these protests see Luis Othoniel Rosa, “Pensar en panal: Apuntes sobre las protestas masivas en Puerto Rico, Julio 2019,” first published in Puerto Rico Review (http://www.thepuertoricoreview.com/rickyrenuncia) and later in Ediciones Mimesis, August 7, 2019.

Author Bio:

Juan Carlos Quiñones (Río Piedras, Puerto Rico, 1972) is a novelist, essayist, translator, and editor. He studied literature and philosophy at the University of Puerto Rico. His texts have been published in Puerto Rican, Latin American, Spanish, and North American magazines and anthologies, both in print and electronically. He is a regular contributor to the magazine 80 Grados+, Revista Plenamar (Dominican Republic), and was a co-editor of the Latin American electronic literary magazine Letralia. In addition to the novel Adelaida recupera su peluche (How Adelaida Got Her Stuffed Toy Back) he has published the prose books Breviario and Todos los nombres el nombre (All The Names in a Name), the novel Bar Schopenhauer, and the children’s novel El libro del tapiz iluminado (The Book of Illuminated Tapestry). His books have been recognized in the competitions of the Pen Club of Puerto Rico, El barco de vapor, and the Institute of Puerto Rican Literature.

How to Cite This: Quiñones, Juan Carlos. Review of “El apagón/Aquí Vive Gente,” by Bad Bunny, JAE Online. This music video was released on September 16, 2022. It is an audiovisual project and documentary directed by Kacho Lopez Marii and incorporating reporting by journalist Bianca Graulau.

Review: Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore:Rethinking the 21st Century Public School

Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore:Rethinking the 21st Century Public School

Nicole King

Review:

ERKIN ÖZAY

ROUTLEDGE, 2020

Nicole King

Review:

ERKIN ÖZAY

ROUTLEDGE, 2020

Many hopes and promises of “fixing” today’s struggling cities center on the twenty-first-century public school as a potential panacea. In Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore: Rethinking the 21st Century Public School, Erkin Özay uses the Henderson-Hopkins school campus in East Baltimore as a case study to analyze and unpack the promises of urban renewal. Henderson-Hopkins, which opened in 2014, was the first new public school in East Baltimore in over twenty years and a great deal depended on its success. Özay deftly explores the role of public schools in attempts to address decades of disinvestment and decline in Black neighborhoods while acknowledging the limits of what public schools can provide. Özay makes it clear that no one school, no matter how innovative, can address the trauma from decades of racial segregation and disinvestment. However, the book shows those in power attempting to use design to counter the effects of development with displacement as they try to rebuild better.

Özay shows that the material realities did not always reflect the lofty ideals. The author writes on page 5: “Led by high-minded ideals of city and school building, the case reveals the potencies and fault lines in our current thinking on the role of the public school as an instrument of urban redevelopment in distressed neighborhoods.” As the first city to legalize neighborhood segregation in 1910, Baltimore also, according to historian Emily Lieb, used public schools to initiate and sustain neighborhood segregation.1 Public school segregation drove neighborhood segregation and, therefore, reforming public education serves as a logical tactic to shift and refocus how we envision cities today.

Özay provides the history and broad context of the immense East Baltimore Development, Inc. (EBDI), an initiative founded in the first years of the twenty-first century. Nearly $2 billion has been invested in EBDI. It has served as a model of redevelopment through “eds and meds,” where institutions of higher education and hospitals act as anchors and catalysts for rebuilding cities. In recent scholarship, EBDI has also served as a representative case of development with displacement as the poor and Black Middle East neighborhood was largely demolished and transformed into Eager Park. EBDI led the extensive redevelopment efforts surrounding the Johns Hopkins Medical Campus and the creation of the Henderson-Hopkins school, itself a redevelopment project of massive scale.

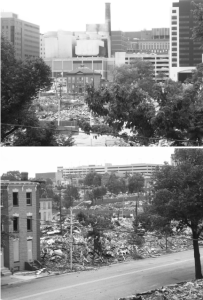

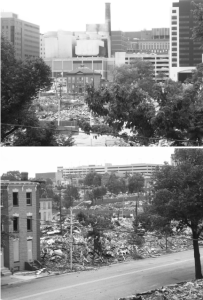

Figure 1. Demolitions on Castle Street, July 2014. In the background is a Hopkins-affiliated garage ramp bridging over the street—an extension of what the Middle East residents called “the wall.” Image © Pat Gavin. [Urban Renewal, 7]

Figure 1. Demolitions on Castle Street, July 2014. In the background is a Hopkins-affiliated garage ramp bridging over the street—an extension of what the Middle East residents called “the wall.” Image © Pat Gavin. [Urban Renewal, 7]

The book is comprehensive, interdisciplinary, meticulously organized, and readable. The first chapter goes over the history that led East Baltimore to a crisis and the narratives of community-focused development and education that offered potential solutions. In the next chapter, the author gives an excellent summary of the rise of the EBDI development and its many players. The third chapter addresses the emergence of the community school as a way to recalibrate this massive development project towards the community. Chapter 4, “A New Park and a New School,” delves deepest into the design and built environment that emerged from the lofty rhetoric and the attempt to be less top-down. This chapter includes numerous maps, renderings, and photographs. The final chapter locates the East Baltimore case study within the scope of similar initiatives in the comparable cities of Detroit and Milwaukee.

Özay locates the planning and construction of the Henderson-Hopkins campus and its innovative design within both the history of the redevelopment and contemporary debates. The book blends analysis of urban design, architecture, and education policy. It begins by exploring why this school matters for those debates. The push for a new public school in East Baltimore was something community organizers and developers could agree on as a potential public good. Community organizers like Lucille Gorham are central in understanding both resistance and the human costs of displacement. Baltimore’s Mayor when EBDI was founded, Martin O’Malley, leaders from Johns Hopkins University, and powerful non-profits involved in the development project all saw the extensive displacement of Black residents as a “bitter but necessary first step” (5).

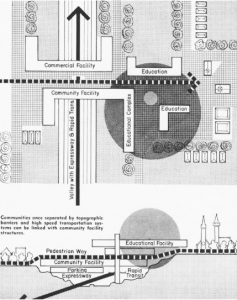

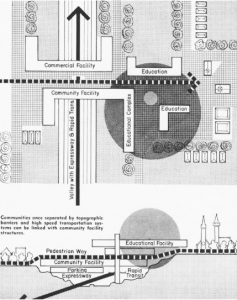

Figure 2. An example of an integrated and expanded conception of an educational facility in Pittsburgh, proposed by Urban Design Associates. The firm prepared the first East Baltimore Development Initiative master plan in 2001. Source: Urban Design Associates . [Urban Renewal, 12]

Figure 2. An example of an integrated and expanded conception of an educational facility in Pittsburgh, proposed by Urban Design Associates. The firm prepared the first East Baltimore Development Initiative master plan in 2001. Source: Urban Design Associates . [Urban Renewal, 12]

The design of the Henderson-Hopkins campus was intended to work with and reflect the feedback of the community; however, much of the community had been displaced and dispersed. EBDI hired consultants to try and track down those who were displaced from earlier stages of the redevelopment, without much success. The school’s design was an innovative and iterative process. The traditional classroom model was replaced by a more open and malleable group of common spaces with moveable “huts.” Flexible learning areas and smaller, more integrated classrooms and open spaces were implemented, but they demanded a great deal from educators and students. It becomes clear that it was far easier to tear things down than to rebuild them in East Baltimore.

Figure 3. Middle East after demolitions, August 2006. Image © Janne Corneil. [Urban Renewal, 77]

One strength of the book is that it develops characters, from the community organizers to the university presidents involved. Rather than voice a tirade against a redevelopment project that did not realize its social goals, Özay shows what had potential and what failed. The vision was not truly collaborative. A major flaw was in perspective—specifically the inability of developers to truly see Middle East and its residents when designing Edgar Park. Quoting Donte Hickman, an East Baltimore pastor, Özay writes: “the EBDI endeavor changed how East Baltimore communities perceived urban interventions, often raising the question, ‘Who are you building for?’” (120). This is a central question in the book and one that is still heard throughout Baltimore and cities like it today.

Özay’s case study of the Hopkins-Henderson campus provides insight to better envision the human potential already within the urban landscape. Still, at the conclusion of the book, the reader is left wondering why cities continue to focus on failed redevelopment plans that cannot see a community as an asset until it has been wiped from the landscape. Books like this one get us to reflect on the process of redevelopment, design, and the public good. Part of that ongoing and iterative process is for scholars and policy makers to learn to see what is already on the landscape. Such studies may provide us with a deeper understanding of urban redevelopment and design based on seeing one another’s humanity and thinking more critically about what we lose before we start tearing things down.

Notes:

Emily Lieb, “’Shove Those Black Clouds Away!’: Jim Crow Schools and Jim Crow Neighborhoods in Baltimore before Brown,” in Baltimore Revisited: Stories of Inequality and Resistance in a U.S. City, ed. P. Nicole King, Kate Drabinski, and Joshua Clark Davis (Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 24–36.

Nicole King, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of American Studies and director of the Orser Center for the Study of Place, Community, and Culture at UMBC. Her research focuses on issues of place, power, and economic development. She is an editor of the book Baltimore Revisited: Stories of Inequality and Resistance in a U.S. City (Rutgers University Press, 2019).

How to Cite This: King, Nicole. Review of Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore: Rethinking the 21st Century Public School, by Erkin Özay, JAE Online, April 22, 2022.

Özay shows that the material realities did not always reflect the lofty ideals. The author writes on page 5: “Led by high-minded ideals of city and school building, the case reveals the potencies and fault lines in our current thinking on the role of the public school as an instrument of urban redevelopment in distressed neighborhoods.” As the first city to legalize neighborhood segregation in 1910, Baltimore also, according to historian Emily Lieb, used public schools to initiate and sustain neighborhood segregation.1 Public school segregation drove neighborhood segregation and, therefore, reforming public education serves as a logical tactic to shift and refocus how we envision cities today.

Özay provides the history and broad context of the immense East Baltimore Development, Inc. (EBDI), an initiative founded in the first years of the twenty-first century. Nearly $2 billion has been invested in EBDI. It has served as a model of redevelopment through “eds and meds,” where institutions of higher education and hospitals act as anchors and catalysts for rebuilding cities. In recent scholarship, EBDI has also served as a representative case of development with displacement as the poor and Black Middle East neighborhood was largely demolished and transformed into Eager Park. EBDI led the extensive redevelopment efforts surrounding the Johns Hopkins Medical Campus and the creation of the Henderson-Hopkins school, itself a redevelopment project of massive scale.

Figure 1. Demolitions on Castle Street, July 2014. In the background is a Hopkins-affiliated garage ramp bridging over the street—an extension of what the Middle East residents called “the wall.” Image © Pat Gavin. [Urban Renewal, 7]

Figure 1. Demolitions on Castle Street, July 2014. In the background is a Hopkins-affiliated garage ramp bridging over the street—an extension of what the Middle East residents called “the wall.” Image © Pat Gavin. [Urban Renewal, 7]The book is comprehensive, interdisciplinary, meticulously organized, and readable. The first chapter goes over the history that led East Baltimore to a crisis and the narratives of community-focused development and education that offered potential solutions. In the next chapter, the author gives an excellent summary of the rise of the EBDI development and its many players. The third chapter addresses the emergence of the community school as a way to recalibrate this massive development project towards the community. Chapter 4, “A New Park and a New School,” delves deepest into the design and built environment that emerged from the lofty rhetoric and the attempt to be less top-down. This chapter includes numerous maps, renderings, and photographs. The final chapter locates the East Baltimore case study within the scope of similar initiatives in the comparable cities of Detroit and Milwaukee.

Özay locates the planning and construction of the Henderson-Hopkins campus and its innovative design within both the history of the redevelopment and contemporary debates. The book blends analysis of urban design, architecture, and education policy. It begins by exploring why this school matters for those debates. The push for a new public school in East Baltimore was something community organizers and developers could agree on as a potential public good. Community organizers like Lucille Gorham are central in understanding both resistance and the human costs of displacement. Baltimore’s Mayor when EBDI was founded, Martin O’Malley, leaders from Johns Hopkins University, and powerful non-profits involved in the development project all saw the extensive displacement of Black residents as a “bitter but necessary first step” (5).

Figure 2. An example of an integrated and expanded conception of an educational facility in Pittsburgh, proposed by Urban Design Associates. The firm prepared the first East Baltimore Development Initiative master plan in 2001. Source: Urban Design Associates . [Urban Renewal, 12]

Figure 2. An example of an integrated and expanded conception of an educational facility in Pittsburgh, proposed by Urban Design Associates. The firm prepared the first East Baltimore Development Initiative master plan in 2001. Source: Urban Design Associates . [Urban Renewal, 12]The design of the Henderson-Hopkins campus was intended to work with and reflect the feedback of the community; however, much of the community had been displaced and dispersed. EBDI hired consultants to try and track down those who were displaced from earlier stages of the redevelopment, without much success. The school’s design was an innovative and iterative process. The traditional classroom model was replaced by a more open and malleable group of common spaces with moveable “huts.” Flexible learning areas and smaller, more integrated classrooms and open spaces were implemented, but they demanded a great deal from educators and students. It becomes clear that it was far easier to tear things down than to rebuild them in East Baltimore.

Figure 3. Middle East after demolitions, August 2006. Image © Janne Corneil. [Urban Renewal, 77]

One strength of the book is that it develops characters, from the community organizers to the university presidents involved. Rather than voice a tirade against a redevelopment project that did not realize its social goals, Özay shows what had potential and what failed. The vision was not truly collaborative. A major flaw was in perspective—specifically the inability of developers to truly see Middle East and its residents when designing Edgar Park. Quoting Donte Hickman, an East Baltimore pastor, Özay writes: “the EBDI endeavor changed how East Baltimore communities perceived urban interventions, often raising the question, ‘Who are you building for?’” (120). This is a central question in the book and one that is still heard throughout Baltimore and cities like it today.

Özay’s case study of the Hopkins-Henderson campus provides insight to better envision the human potential already within the urban landscape. Still, at the conclusion of the book, the reader is left wondering why cities continue to focus on failed redevelopment plans that cannot see a community as an asset until it has been wiped from the landscape. Books like this one get us to reflect on the process of redevelopment, design, and the public good. Part of that ongoing and iterative process is for scholars and policy makers to learn to see what is already on the landscape. Such studies may provide us with a deeper understanding of urban redevelopment and design based on seeing one another’s humanity and thinking more critically about what we lose before we start tearing things down.

Notes:

Emily Lieb, “’Shove Those Black Clouds Away!’: Jim Crow Schools and Jim Crow Neighborhoods in Baltimore before Brown,” in Baltimore Revisited: Stories of Inequality and Resistance in a U.S. City, ed. P. Nicole King, Kate Drabinski, and Joshua Clark Davis (Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 24–36.

Nicole King, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of American Studies and director of the Orser Center for the Study of Place, Community, and Culture at UMBC. Her research focuses on issues of place, power, and economic development. She is an editor of the book Baltimore Revisited: Stories of Inequality and Resistance in a U.S. City (Rutgers University Press, 2019).

How to Cite This: King, Nicole. Review of Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore: Rethinking the 21st Century Public School, by Erkin Özay, JAE Online, April 22, 2022.